The Tax Reform Act of 1969 provided the legal framework for much of what gift planners do today. To reform abuses of loosely regulated charitable trusts and private foundations, the Act mandated many new rules. For example:

The Tax Reform Act of 1969 provided the legal framework for much of what gift planners do today. To reform abuses of loosely regulated charitable trusts and private foundations, the Act mandated many new rules. For example:

- For charitable remainder trusts to qualify for favorable tax treatment, the Act required the use of new unitrust and annuity trust forms, a 5% minimum payment, and a four-tier system for recognizing taxable income

- Private foundations were compelled to make much larger grant distributions than many had been doing. As a result, the Lilly Endowment was able to provide financial support for a number of gift planning initiatives, including the founding and development of the National Committee on Planned Giving, predecessor of the National Association of Charitable Gift Planners

These and other changes in the law had a powerful impact on the practice of charitable gift planning. While familiar tools such as charitable remainder trusts and lead trusts, pooled income funds, and gift annuities were in use long before 1969, the new legislation spelled out very specific and wide-ranging new rules for their operation.

These new rules forced a break with previous laws and traditions. The Tax Reform Act of 1969 was America’s first statement of comprehensive policies on charitable gift planning. Experienced gift planners were forced to learn a complex new system of legal requirements. A considerable amount of research and experience would be needed to understand the law, ensure compliance, and realize new gift opportunities.

The Act created an immediate demand for professional training, publications, and networking. It soon became clear to donors and gift planners that safe harbors for permissible gift arrangements would lead to more and larger gifts, and that the charitable remainder value of planned gifts would be better protected against abuses.

As a result of the Tax Reform Act, many people became attracted to the field of charitable gift planning. Gift planning councils sprang up across the country. Another major tax reform in 1986 closed many popular loopholes, making charitable remainder trusts even more attractive, and intensifying the need for a national professional association. The National Committee on Planned Giving (now NACGP) was founded as a federation of gift planning councils in 1988.

Gift planners continue to find creative gift arrangements within the legal framework set out in 1969.

This is an anniversary worth celebrating!

Why Were Charitable Trust and Foundation Reforms Needed?

It would be wrong to assume that in planning their hearings on a tax reform bill in January of 1969, members of Congress had deeply considered the needs of America’s nonprofits, analyzed all the available fund raising arrangements, and envisioned an ideal system for encouraging planned gifts.

The opposite is true: as hearings began, Congress intended to end certain widely-reported and sensationalized abuses of charitable trusts and foundations. The first witness called by the U.S. House Ways and Means Committee was Wright Patman (D-Texas), whose opening statement made clear he intended not to create, but to eradicate:

Today, I shall introduce a bill to end a gross inequity which this country and its citizens can no longer afford: The tax-exempt status of the so-called privately controlled charitable foundations, and their propensity for domination of business and accumulation of wealth.

Put most bluntly, philanthropy – one of mankind’s more noble instincts – has been perverted into a vehicle for institutionalized, deliberate evasion of fiscal and moral responsibility to the Nation.

For seven years before 1969, Patman’s Congressional hearings and reports detailed allegations of self-dealing, political corruption, and Communist infiltration (a prominent example was Alger Hiss, forced to resign as president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace). Increasing scrutiny by Patman, the U.S. Treasury Department, and the media raised the specter of a ban on charitable trusts and foundations. New rules were necessary to protect legitimate uses.

The most common abuse of foundations was self-dealing: hiring family members as well-paid staff with no actual responsibilities; making personal loans at no interest that were never repaid; making grants to family and friends for study or travel; using a foundation to acquire a controlling interest in a profit-making company and protect against hostile buyouts; transferring real estate and tangible property to a foundation, but retaining the use and enjoyment of the property.

Foundation abuses were well-known. A popular book entitled How Tax Laws Make Giving to Charity Easy by J.K. Lasser (1948) provided clear advice that could have been a road-map for legislators seeking reforms in 1969:

By giving to a foundation the donor can keep many attributes of his wealth … If [his gifts] consist of shares of stock, he controls them in almost every respect as though he still owns them … Some donors exercise control that goes even further. They appoint relatives as directors of the foundation to insure control by persons closely acquainted with the desires of the donor. Some arrange for the administrators to be family members who receive substantial compensation so that the contributed wealth really yields substantial income … One man who created a Rhode Island foundation later went into a new business. He used the trust to borrow money to buy textile mills that were later sold to his company. Thus, he benefitted materially from the capitalized credit of the foundation he created.

The Blue Book prepared by Congressional staff of the Joint Committee on Internal Revenue Taxation as a General Explanation of the 1969 Tax Reform Act illustrated abuses of loosely regulated life income trust arrangements. For hundreds of years, most life income trusts had paid their net income to noncharitable beneficiaries, with the remainder used for charitable purposes. By law in the 1960s, annual trust payments were assumed to be 3.5% in computing the charitable deduction, but some trusts were invested in high-yield assets resulting in much greater income for beneficiaries and a depletion of the principal remaining for charity.

Donors could claim charitable deductions even when a charity had only a contingent interest in the trust: for example, a $5,000 annuity to A for life, remainder to her/his children, or to charity if A had no children. Some trusts permitted invasion of trust principal in order to maintain a beneficiary’s standard of living.

A particularly sore point among Congressmen was that in the 1960s the financial benefit from making a gift of appreciated property to a charitable organization could be a bit greater than from selling the property and paying capital gain taxes.

A few donors avoided income taxes through a legally-permitted 100% charitable deduction. Early in the hearings before the Ways and Means Committee, McGeorge Bundy of the Ford Foundation admitted that he had paid no income tax for several years because of his charitable gifts.

America’s First Comprehensive Policies on Charitable Gift Planning

To ensure that the wealthiest Americans could not use charity to avoid paying taxes, Congress would impose new charitable deduction limits of 50% of adjusted gross income (AGI) for outright gifts of cash, 30% for gifts of appreciated property, and 20% for gifts to private foundations, and would enact an Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT).

The Tax Reform Act signed into law by President Richard Nixon on December 30, 1969 contained many other provisions affecting charitable gift planning.

Members of the House and Senate had very little knowledge about the specific techniques of charitable gift planning. Experienced tax attorneys, including John Meck, John Holt Myers, and Conrad Teitell assisted Congressional staff and the Treasury Department in drafting important parts of the Act and its implementing regulations, ensuring that previously-existing gift arrangements such as charitable remainder trusts, pooled income funds, and gift annuities were addressed appropriately.

To protect the charitable remainder interest for which life income gifts qualified for favorable tax treatment, these gifts were limited to four standardized arrangements: charitable remainder unitrusts, charitable remainder annuity trusts, pooled income funds, and charitable gift annuities. There were newly defined unitrust provisions for net-income and make-up payments. Other life income arrangements no longer qualified for charitable deductions. Charitable lead trusts also were limited to annuity and unitrust arrangements.

Charitable remainder trusts and private foundations became subject to rules against self-dealing, prohibiting certain interactions with disqualified persons, retaining excess business holdings, and participating in jeopardy (high-risk) investments. These reforms continue to protect the public interest today as private foundations, trusts, and donor-advised funds receive mega-gifts and bequests worth billions of dollars.

Under the lax rules governing charitable lead trusts and life-income gifts before 1969, some wealthy donors had evaded gift and estate taxes by naming a third or fourth generation (grandchildren or great-grandchildren) as beneficiaries. In order to ensure that wealth was taxed as it passed down to each generation, Congress imposed a Generation-Skipping Transfer Tax (GSTT), and required that named beneficiaries must be alive at the time a charitable trust is funded.

Income beneficiaries were prevented from manipulating the tax treatment of trust payouts through a four-tier system (ordinary income, capital gains, tax-free income, and tax-free return of principal).

Lilly Endowment Provided National Leadership in Charitable Gift Planning

The Tax Reform Act of 1969 compelled many foundations to increase their grants by imposing a mandatory distribution requirement: private foundations (as well as charitable remainder trusts) were required to pay out a minimum of 5% annually.

As was common for foundations that were closely tied to the wealth generated by a family corporation, the Lilly Endowment in Indianapolis invested primarily in low-yielding Eli Lilly and Company stock. Of great importance for the field of charitable gift planning, the Act resulted in the Lilly Endowment tripling the amount of its annual grants.

As a result of Lilly’s interest in gift planning, and thanks to the leadership and advocacy of Charles Johnson, its Vice President for Development, between 1978-1983 Lilly provided major grants to support planned giving programs among colleges in Indiana, theological seminaries, historically black colleges and universities, the Girl Scouts, and community foundations. Lilly provided funding to develop the Certified Fund Raising Executive (CFRE) program and to publish an influential report on The Costs and Benefits of Deferred Giving (1982).

Perhaps most important for the profession of charitable gift planning, between 1987-1992 Lilly provided six grants totaling $412,500 to create and support the National Committee on Planned Giving (now NACGP). Lilly also provided a start-up grant of $4 million in 1987 for the Center on Philanthropy in Indianapolis, which became the administrative sponsor for NCPG.

Impacts of the Tax Reform Act of 1969

In an important article in 1970, two expert attorneys helped clarify the new law, while admitting that more guidance was needed:

This article is only the beginning of a new body of thought on the subject of charitable contributions. Proposed regulations on the new provisions will issue shortly to give us the official view of much of the Act that is open to interpretation … many of the answers blithely assumed in this article may turn out to be less than correct.1

A front-page article in the Wall Street Journal on December 29, 1971 reported the frustration felt by donors two years after the massive Act became law:

The sheer complexity of the new rules on “split-interest” trusts has caused some taxpayers to throw up their hands. Where a guy might have said, all the income to my wife, remainder to Harvard, today he’s liable to say, oh, the hell with it. He leaves it all to his wife and gives Harvard $5,000 and Harvard never knows what it has missed.

Taken as a whole, the Act represented an experiment in reforming existing methods of giving, with unknown outcomes. Planners were uncertain about how to comply with the new safe harbors, and how the rules for gift forms, taxation, valuation, self-dealing, and timing should interact.

Recognizing the complexities, in Revenue Ruling 72-395 the IRS issued sample provisions to be included in the governing instruments of qualified charitable remainder trusts. The IRS would issue a model set of unitrust and annuity trust agreements much later, in 1989 and 1990. Gift planners criticized the templates as incomplete.

Uncertainty over the implications of the Act, especially before enabling regulations were written by the Treasury Department, contributed to a slowdown in new charitable remainder trust and pooled income fund gifts in 1970-1971, compared with planned gifts received in the 1960s. Several years passed, while gift planners worked diligently to master the technical details, publish reference materials, amend existing gift arrangements for compliance, adopt and inform donors about new gift forms, and add or train specialized staff at nonprofit organizations.

Once people understood the new opportunities, a great wave of interest in gift planning swept across the United States. In 1972, planned giving increased dramatically to pre-1969 levels. The Survey of Voluntary Support of Education 1971-72 noted the country’s reaction to the Act:

Deferred gifts, which had declined substantially in the previous three years, rose 70% to a new record . . . Total support in the form of annuity trusts, life income contracts, insurance policies, and other forms of deferred giving amounted to $51.2 million in 1971-72 . . . This amount constituted 6.4% of total support received from individuals, the highest percentage figure since 1967-68.

Testimony given at the House and Senate hearings in 1969 had shown the need for more information about the nonprofit sector of the American economy. Nonprofits wanted to be better prepared for Congressional oversight and public accountability, to clarify their roles for themselves and for policymakers, and to stimulate more generous giving. That led to the creation of the Commission on Private Philanthropy and Public Needs (better known as the Filer Commission) in 1973, which spawned 86 research projects over the next two years and a final report on Giving in America: Towards a Stronger Voluntary Sector (1975).

In 1974 the Northwest Area Foundation in Minneapolis gave grants to help 18 colleges and universities begin planned giving programs. A second round of grants in 1977 funded 11 more programs. In 1985, the foundation reported combined total results of 7,010 planned gifts with a face value of $237 million. A number of new leaders of the planned giving profession began their careers as a function of these new programs and others funded by the Lilly Endowment.

A pressing need for more and better professional training and support led to the founding of local and regional planned giving councils between 1971-1986. In January 1986, Charles Johnson of the Lilly Endowment listed ten existing councils; there were several others not known to him. In July, 2019 more than 8,000 people belonged to 97 gift planning councils affiliated with NACGP. There are roughly 3,000 individual members of NACGP.

Our profession of charitable gift planning, and the people served by thousands of nonprofit organizations over the last 50 years, are deeply indebted to the Tax Reform Act of 1969.

Happy anniversary!

1 “Charitable Contributions and Bequests by Individuals: The Impact of the Tax Reform Act” (New York: Fordham Law Review, Vol 39 Issue 2, 1970), John Holt Myers and James W. Quiggle.

Through its Wise Public Giving Series of publications, the Committee encouraged charitable gifts through outright gifts, wills, trusts, annuities, and other methods. For example, in 1927 the Committee published a pamphlet encouraging the use of charitable life income trusts, now known as charitable remainder trusts, entitled Living Trusts: What They Are, What They Serve, Their Advantages. The pamphlet includes a sample life income trust agreement. Living trusts were said to be “good for those who wish an income for themselves or others without the responsibility of administering property.”

Through its Wise Public Giving Series of publications, the Committee encouraged charitable gifts through outright gifts, wills, trusts, annuities, and other methods. For example, in 1927 the Committee published a pamphlet encouraging the use of charitable life income trusts, now known as charitable remainder trusts, entitled Living Trusts: What They Are, What They Serve, Their Advantages. The pamphlet includes a sample life income trust agreement. Living trusts were said to be “good for those who wish an income for themselves or others without the responsibility of administering property.”

About 1,800 gift planners participated in 13 national conferences held by the Committee on Gift Annuities (ACGA) before the Tax Reform Act of 1969. Its 34th conference will be held in April 2020.

About 1,800 gift planners participated in 13 national conferences held by the Committee on Gift Annuities (ACGA) before the Tax Reform Act of 1969. Its 34th conference will be held in April 2020.

One of the earliest comprehensive gift planning programs began in 1937 when Stanford University started its long-running R-Plan (named for its founder, State Senator Louis H. Roseberry), including a Cardinal-colored reference binder for donors and professional advisors interested in charitable gift planning.

One of the earliest comprehensive gift planning programs began in 1937 when Stanford University started its long-running R-Plan (named for its founder, State Senator Louis H. Roseberry), including a Cardinal-colored reference binder for donors and professional advisors interested in charitable gift planning.

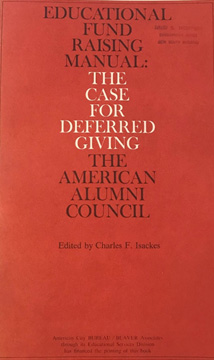

By 1968, a full toolbox was available for gift planners: bequests, life income trusts, pooled income funds, lead trusts, gift annuities, gifts of complex assets, private and public community foundations, donor-advised funds, and supporting organizations. Gift planning was encouraged by the National Council of Churches, the Association of American Colleges, the Committee on Gift Annuities (ACGA), tax attorneys and consultants specializing in gift planning, banks, life insurance and trust companies, alumni associated with many college bequest and trust programs, and a growing number of reference publications.

By 1968, a full toolbox was available for gift planners: bequests, life income trusts, pooled income funds, lead trusts, gift annuities, gifts of complex assets, private and public community foundations, donor-advised funds, and supporting organizations. Gift planning was encouraged by the National Council of Churches, the Association of American Colleges, the Committee on Gift Annuities (ACGA), tax attorneys and consultants specializing in gift planning, banks, life insurance and trust companies, alumni associated with many college bequest and trust programs, and a growing number of reference publications. The Tax Reform Act of 1969 provided the legal framework for much of what gift planners do today. To reform abuses of loosely regulated charitable trusts and private foundations, the Act mandated many new rules. For example:

The Tax Reform Act of 1969 provided the legal framework for much of what gift planners do today. To reform abuses of loosely regulated charitable trusts and private foundations, the Act mandated many new rules. For example:

You must be logged in to post a comment.