When did American gift planning begin?

Written records are the basic materials of historians. Unfortunately, no records of charitable giving by Native American populations before European settlement have survived. Little is known about the settlers at Roanoke, North Carolina in the 1580’s.

America’s earliest immigrants continued a long tradition of providing a bequest to charity: four Mayflower Pilgrims made gifts to their churches through their written wills in the 1600’s.

Mary Chilton Winslow, one of the first of the Pilgrims to step ashore at Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1620, left a bequest to her church through her will. Born in England, and just 13 years of age when her feet splashed down in the New World, Mary lived a full life, gave birth to ten children, and died in 1679. Among her descendants is the late President George Herbert Walker Bush.

One of the earliest American charitable bequests was in the year 1621, when Reverend Thomas Bargrave bequeathed his library to a proposed college in Virginia. If we were celebrating Bargrave College as America’s first, his bequest might be famous today. But in 1622, the gentleman sent from England to be superintendent of the college was killed by Powhatan Indians. Plans were put on hold until 1693, when a charter was granted to The College of William and Mary, colonial America’s second college. The fate of Bargrave’s library is unknown.

The first college in the American colonies, and one of our earliest nonprofit organizations, is Harvard College, founded in 1636. John Harvard, an Englishman educated at Cambridge, emigrated with his wife Ann to Massachusetts in 1637 at age 29 and died the next year. In addition to his library of 400 volumes, John Harvard bequeathed about 800 pounds to the college – very large gifts for the time. Grateful trustees renamed the college in honor of his bequest.

As America’s only college for 57 years, Harvard documented early examples of many planned gifts. Harvard was a beneficiary in the will of Robert Keayne, a Boston merchant, whose Apologia, written in 1653, occupies 158 pages in the probate records. Keayne bequeathed substantial gifts to the Boston community: a conduit to combat fires; a town house with a market and library; an artillery range, and “two heifers or cows to the captain and officers of the First Artillery Company to be kept as a stock constantly and the increase or profit of these cows yearly to be laid out in powder or bullets, etc., for the use and exercise of the great artillery”; 50 pounds for a school “to help with the training up of some poor men’s children of Boston (that are most towardly and hopeful) in the knowledge of God and of learning”; 50 pounds “for the use and relief of the poor members of our own church or to any other good use that shall be accounted as necessary.”

Keayne, who felt unfairly accused of profiteering at the expense of his neighbors, added a caveat: “if the town of Boston shall slight or undervalue this gift or my good will to them therein and shall refuse or neglect to go about and finish these several buildings” his bequest will go instead “to the sole use of the College at Cambridge.” To ensure a benefit for Harvard College, he added that if Boston observed the conditions of his bequests for public works (it did), his estate provided an annuity of 20 pounds per year to Harvard “for the best good of the scholars.” His annuity payments to the college were realized.

Keayne, who felt unfairly accused of profiteering at the expense of his neighbors, added a caveat: “if the town of Boston shall slight or undervalue this gift or my good will to them therein and shall refuse or neglect to go about and finish these several buildings” his bequest will go instead “to the sole use of the College at Cambridge.” To ensure a benefit for Harvard College, he added that if Boston observed the conditions of his bequests for public works (it did), his estate provided an annuity of 20 pounds per year to Harvard “for the best good of the scholars.” His annuity payments to the college were realized.

Harvard College encouraged bequests from the time of its founding. Between 1636-1712, bequests provided about three times as much money for Harvard as did gifts from living individuals.

All American colleges from 1636 to our independence depended on bequests. Princeton University’s charter in 1746 included the power “to receive legacies and bequests of any kind whatsoever.” When the founders drafted the charter, they knew that a sizeable bequest for a new college to be located in New Jersey had been pledged in 1745 in the will of James Alexander, a leading New Jersey power broker and attorney.

Alexander’s public commitment to a bequest was very important to the founding of Princeton (originally known as The College of New Jersey). It provided the founders with confidence in their project; it gave credibility to the proposed college; and it helped to attract other donors.

The first bequest received by Princeton was recorded in the Trustee minutes on September 27, 1749: five pounds from the estate of Evan Revis. A very large bequest to Princeton in the amount of 700 pounds from William Kings of Delaware was reported in the Boston Gazette on April 24, 1750.

Another bequest donor is more famous. The bequest to Princeton from Jonathan Belcher, the Provincial Governor of New Jersey and President of the college’s Board of Trustees, may be well-known, but not many people are aware of the complex arrangements for his gift.

Belcher pledged his book collection, a number of paintings, and his “terrestrial globes” to the college. His gifts were arranged through a formal legal contract, recorded in the Trustee’s minutes of May 8, 1755. Governor Belcher received consideration of ten shillings from the College for his pledge, “reserving for myself nevertheless the Possession & Use of all the aforegoing Premises during my natural life.”

This is a good example of the sophistication of gift arrangements available to donors in America’s colonial era.

Governor Belcher’s legally-binding pledge of a bequest, made during the fund raising campaign to build the College campus, inspired the Trustees to offer to name its main campus building “Belcher Hall.”

As a member of the Harvard Class of 1699, Belcher was mindful of John Harvard’s bequest, which named that college more than a century earlier. But the Governor modestly refused the Trustees’ offer, and suggested the building be named Nassau Hall in honor of King William the Third of the House of Nassau.

The College took possession of Belcher’s gifts after the Governor’s death in 1757, at which time Princeton received the globes, paintings, and 474 books, making the college library one of the largest in the American colonies.

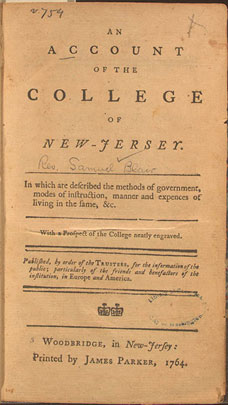

Rev. Samuel Blair, Jr. graduated with the Princeton Class of 1761, then was hired as a tutor. Blair wrote a fund raising pamphlet entitled An Account of the College of New-Jersey which was published in 1764.

Rev. Samuel Blair, Jr. graduated with the Princeton Class of 1761, then was hired as a tutor. Blair wrote a fund raising pamphlet entitled An Account of the College of New-Jersey which was published in 1764.

In it he mentioned a bequest in the works from the estate of Colonel Alford of Massachusetts that could be as much as 500 pounds. At the time, the annual cost for a Princeton student’s tuition, fees, room, board, and other expenses was just over 25 pounds.

Blair included this sample language for a bequest to Princeton:

I do hereby give and bequeath the Sum of [X dollars] unto the Trustees of the College of New-Jersey, commonly called Nassau Hall.

Throughout U.S. history, bequests have provided more financial support for nonprofit charitable organizations than all other gifts through trusts, annuities, and complex assets combined. Bequests made possible the Smithsonian Museum, the Pulitzer Prize, hospitals, homeless shelters, wildlife refuges, schools, colleges, churches, synagogues, and other nonprofits. According to Giving USA, charitable bequests provided $39.7 billion in 2018. Charitable remainder trusts, gift annuities, lead trusts, and gifts of complex assets provided $8-10 billion that year.